And even if the post-interval portions don’t quite measure up, the visual energy keeps us watching. Along with the hero who owns the now-legendary ‘dhai kilo ka haath’. The rest of this review may contain spoilers.

It’s the season for political references in our big-star masala movies. If Empuraan went back to the 2002 violence in Gujarat, which is still contentious, Sunny Deol’s Jaat finds its villain in the Sri Lankan Civil War, making the still-contentious claim that the Tigers were terrorists. This villain’s name is Ranatunga, and he’s played by Randeep Hooda in full-on savage-menace mode. I think more of our serious actors should give in to the pleasures of the masala movie, at least once in a while. The man is wildly magnetic. Given his place of origin, Ranatunga is the Ravana of this movie, while the hero gets his introduction on an Ayodhya-bound train filled with devotees singing the praises of Rama. Due to an accident (or due to divine intervention), the train stops near the place where Ranatunga and his men have unleashed their reign of terror. And the showdown begins.

The basic, age-old one-line of Gopichand Malineni’s movie is from Kurosawa’s Yojimbo: a random man (with no love interest) wanders into a random town where bad men live, and he puts an end to the badness. And the first half is a masterclass in masala-cinema writing. You know the hero has to meet the villain, but Jaat makes us wait for it through a very funny running joke that keeps on giving. The hero meets a villain lower down the rungs, then one slightly higher-up, and then one who’s even more up the ladder, and only then does he stand face to face with Ranatunga. At a time when so many of our masala movies are just a loose collection of hero-elevation scenes, Jaat builds up, step by step, to the confrontation between Good and Evil. There is not a single wasted scene and each development segues neatly into the next one and escalates the drama. Bravo!

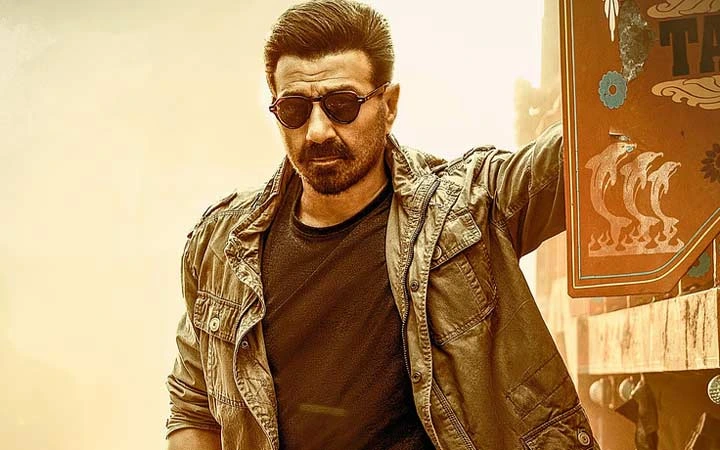

Every department pitches in. There is a super-cool stunt where Ranatunga hangs upside down and becomes a sort of helicopter, doing a 360-degree turn with knives in his hands slashing the throats of his opponents. There is a lot of that in this movie – beheadings, the cutting of thumbs, and other such blood-soaked joys. I find it refreshing that we are moving away from the cartoonish dishoom-dishoom violence of our older films and drawing real blood. This really helps to raise the stakes. (The darkish colour palette helps, too.) On the other hand, the film doesn’t forget to wink at its leading man and his water-pump stunt in Gadar. This is the fun, cartoonish part, where Sunny Deol turns into a bulldozer (his nickname in the movie) and uproots and demolishes everything in sight with nothing more than his “dhai kilo ha haath”. The role fits the actor like a dhai kilo ka glove.

But it’s also frustrating that every time a bad guy wants to teach a woman a lesson, he disrobes her. There’s a nice retaliation scene where one such woman wields a fire extinguisher on her attacker, between his legs, after announcing that unlike a man, a woman’s honour is not between her legs. But the other women are just generic victims, and their scenes leave a sour taste in the mouth. I loved the touch that it’s not just men, but that women can be evil, too. Regina Cassandra plays Ranatunga’s wife, and what she does in her first big scene is a shocker. Ranatunga’s aged mother, too, is no slouch. In her first big scene, she is terrorising a bunch of government officials into notarising blank papers. The film is set in coastal Andhra Pradesh, and I liked the mix of languages, especially Hindi, which is spoken with both a Northern and Southern accent.

The second half, though, is disappointing. It turns totally serious, which is another word for seriously predictable. We get the “sad flashback” that explains what Ranatunga did to establish his empire of evil, and then we get the smaller flashbacks that establish who the hero is. And a big plot point is treated idiotically, by having the Regina Cassandra character narrate it to people she is holding captive. Why would such a cruel and clever woman, the only person capable of confronting and defusing Ranatunga’s rage, reveal this information to a bunch of strangers? It feels that, after that terrific first half, the writers lost their energy and settled for the easiest narrative clichés, including patriotism and self-righteousness and Jagapathi Babu playing a CBI officer who lands up at the climax scene later than the police usually do. “Main is mitti se bana jaat hoon,” our hero says, before wiping the floor clean with the Sri Lanka ki mitti se bana villain.

Sunny Deol made his debut in Betaab, but the love story has never been his forte. He excels when he has an omnipotent villain opposite him, who shows off his omnipotence with lip-smacking lines like “Sooraj bhi mujhse garmi maangta hai.” If the second half of Jaat had matched up to the garmi of the first half, we might have had a modern-day masala classic – but even when the film loses energy post interval, it never loses visual energy. Cinematographer Rishi Punjabi gives us a series of cool visuals, where even something like a mass hanging is “presented” to us with flair, with a lovely pan-shot. It’ll be interesting to see if Jaat succeeds, because unlike the South, Hindi cinema does not have the tradition of ageing-yet-potent action heroes. But even with all the flaws and missed opportunities, Jaat is the best Hindi masala movie made by a Southern filmmaker. Even if it doesn’t reinvent the wheel, it proves that there’s still mileage left in this genre.